Lie Nielsen 101 Plane

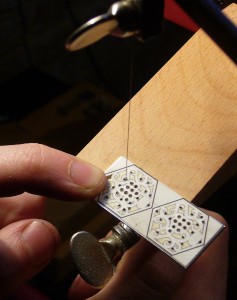

It was my birthday recently, plus I had just been paid for one of my first commissions since I started Holden Concertinas, so I decided to treat myself to something a bit special. A new, high-quality hand tool that will be useful throughout my career as a concertina maker. After a lot of thought I settled on the Lie Nielsen 101 block plane.

It is very loosely based on the Stanley 101, which was apparently originally intended as a child’s toy but proved popular with modelmakers and was widely copied by other manufacturers. It features several improvements that elevate it to the level of a professional tool: a heavy, accurately machined, cast bronze body, fine screw adjustment for depth of cut, and a thick blade made from A2 steel. I normally prefer to save money by buying vintage tools and refurbishing them, but I think this is one case where the modern version really is a lot better (though if I’d had the option, I’d probably have chosen an O1 blade rather than A2 because it takes a slightly finer edge and is easier to sharpen).

Lie Nielsen advertise it as a violin maker’s plane, though I don’t think there is anything about it that makes it especially well-suited for the tasks involved in violin-making. It’s really just a very small, well made block plane. I can see it being useful for many kinds of small-scale woodworking: model boats, doll’s houses, jewellery boxes, musical instruments, etc.

Lie Nielsen advertise it as a violin maker’s plane, though I don’t think there is anything about it that makes it especially well-suited for the tasks involved in violin-making. It’s really just a very small, well made block plane. I can see it being useful for many kinds of small-scale woodworking: model boats, doll’s houses, jewellery boxes, musical instruments, etc.

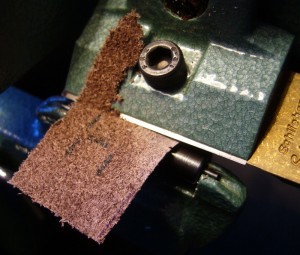

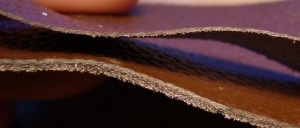

My one complaint with it is that the blade was dull out of the box. The back and bevel appeared to have been surface-ground and perhaps quickly swiped across a medium grit diamond stone. The surface finish was relatively rough and unpolished, and there was a slight burr at the edge. It would cut if you forced it through the wood but it wasn’t a nice experience. I know people have different standards with regards to tool sharpness and my standards are fairly high, but I wonder how many hand-tool beginners buy a high-end tool like this with the expectation that it is going to work really well straight away. They will have a disappointing first experience of the product because it is basically horrible to use until you have learned how to sharpen the blade. Particularly since the instruction leaflet claims, “The blade comes ready to use. Slight additional honing will increase performance.” Really. It’s a bit like a high-end car maker like Mercedes selling a new car with an empty petrol tank and claiming, “The vehicle comes ready to use. The addition of fuel will increase performance.”

There is an interesting parallel between Lie Nielsen’s business model and my own. Most of LN’s tools are basically copies of vintage tools invented by Stanley and others with slight improvements to the design, improved materials, and modern manufacturing methods. The tools aren’t cheap but they are well-made (apart from the dull blade thing) and highly desirable, and as a result their business seems to be very successful.