The sixth instalment in the story of how I built my first concertina is about the reeds. I’m not going to cover every step of the process because it was very similar to my previous posts on the subject, apart from a few minor improvements and the fact that I had to make sixty of them in twenty four different pitches.

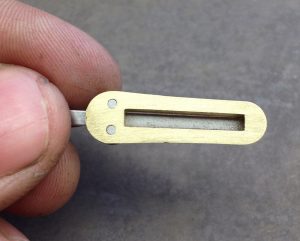

Something unusual I did (it might even be the first time it’s been done by a concertina maker) is I made a different size of frame for every pitch instead of making do with a limited number of frame sizes, each one being used for two, three or even four pitches. I started by measuring the vent dimensions of the reeds in a Lachenal English I own and plotting them on a graph. They were pretty lumpy but they followed a general trend. I then fitted curves to the graph and used them to derive a formula for the reed scaling. I plugged those formulas into a spreadsheet, which calculated the vent dimensions for all the pitches I needed. The outer frames were all the same angle and tip radius, with a constant distance between the tip of the frame and the tip of the vent. A slight drawback with the way I did it is that the longer reeds ended up with thinner edges than the shorter ones; when I design the next set I may try to come up with a way to reduce that effect.

I have since learned that the reeds I based my scale on were probably what is known as “short scale”. A fellow maker sent me a set of measurements of reeds from a higher quality vintage instrument, which appears to have both longer low reeds and shorter high ones, i.e. the range of pitches is stretched out over a wider range of lengths. I understand short scale reeds were typically used when the maker needed to fit a lot of reeds into a given space, which actually makes a lot of sense for this particular instrument because the reed pans are very tightly packed. I don’t think I could have fit long scale reeds in it if I had tried. My next concertina will have the same number of buttons in a larger instrument, so I plan to use longer scale reeds in it. I have been told that longer scale reeds have better pitch stability and responsiveness, particularly on the low end.

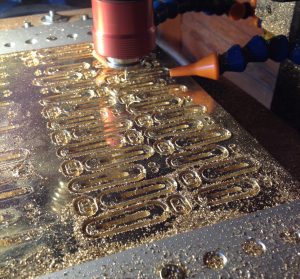

As before, I cut the frames and clamps from 2mm brass sheet on my CNC milling machine. This time I left them at the full 2mm thickness.

When I did the prototype reeds, each frame took a very long time to mill. Before I made the first full set I spent a while experimenting with feed rates and depth of cut (wasted some material and broke a couple of end mills in the process), and came up with a reliable rate that is significantly faster than what I was using before. I also dropped what was by far the slowest part of the process: bevelling the edges of the frames with lots of tiny steps. They now come out of the milling stage with straight sides.

The full set of sixty frames and clamps, before cutting them free of the stock.

After cutting them free, I tapped all 120 clamp holes and screwed them together. The clamp is a different size for each pitch too, so it’s important not to mix them up!

I filed off the flashing and the remains of the tabs with a hand file. In hindsight it would have been quicker to use my die filer to clean up the frames, though the clamps are probably too small to do that way.

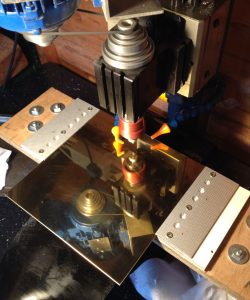

A little improvised fixture to hold each reed frame while I square up the vent corners with a needle file. It’s crucial to get the tip corners as perfect as possible otherwise you can’t get the tongue to fit really closely without clipping the frame.

The vent relief angles on my Lachenal reeds were very inconsistent and often rounded; I suspect they were quickly filed by eye without a guide. I set my guide to an angle that was roughly the average of the angles on the Lachenal reeds and used it for all of my reeds.

I used my die filing machine with the table tilted over to 7.5° to bevel the frame edges, filing up to a line engraved by the CNC mill. I deliberately left them a bit on the tight side, then later on after I’d made the reed pans, I hand fitted each frame to its slot with a hand file.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BTTeGiqjHiH/

I shortened the clamp screws by first clamping the reed tongue blank in the frame, then grinding the screws almost all the way on a slow grinding wheel, followed by lapping them flat on a piece of fine emery paper glued to a sheet of glass.

All the tongues roughly sheared to size.

Draw filing the edges of the tongues to clean them up, then fitting them precisely to their frame with the aid of my microscope. This is probably the most difficult and painstaking part of the process to get right.

All the tongues initially fitted to their frames; many hours of work have gone into them at this point.

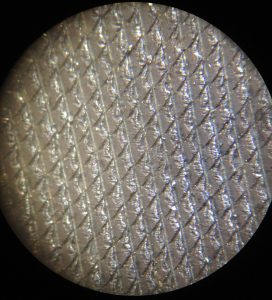

My file was feeling pretty dull so I had a look at it under the microscope. All the teeth had their edges fractured off. No wonder it wasn’t cutting so well any more!

I probably should have bought a new file at this point but I kept going and did much of the profiling with it (I also used a three square file for some of the work). I can’t remember if I’ve written about the fixture in this picture before. It has an adjustable-height step that you place the tongue against. The clamp is a pair of locking pliers that have been modified to have a sharper nose.

The full set of reeds, profiled and rough-tuned. They start out very high initially and go lower as you profile them. I stopped filing when they reached somewhere between +5 and +20 cents sharp on the tuning bench, knowing that they were likely to go a bit flatter once in the instrument. The way they are arranged in this photo shows the unisonoric reed pairs for the left hand on top and the right hand on the bottom, with a few notes of overlap in the middle. If it was an English or Anglo concertina the distribution would look very different.

It’s been said by other makers that, of the many time-consuming stages involved in making an English-style concertina from scratch, the reeds are the greatest. I think I can definitely agree with that statement. I probably spent at least a couple of hours on every reed, maybe more when I include time later spent troubleshooting and fine-tuning.

Hi, Alex – I use single-cut files*); they tend to leave a smoother trail. I would be curious to whether your reeds have the same “bite” (audio: snarl, growl, what-have-you) as an, say, original Wheatstone reed. I find that that is a problem in the low end. Mind, I didn’t make any effort of measuring the original reed and attempt to copy the profile. That will be next time ;-),

Best regards,

/Henrik

*) Bacho/Öberg 158-06-1 and 138-08-1

Thanks Henrik, I’ve been picking up a selection of files to try on my second set of reeds. Bahco are a decent brand, and not too pricey. In the past I’ve found single cut to be a bit less predictable; more likely to suddenly dig in and remove more than I expect.

I can’t really comment on how the tone compares to other instruments, as it’s so subjective and I don’t have a lot of experience with working on or playing good vintage instruments. I do think it has a pleasing sound, but I wouldn’t like to try to describe it.

I didn’t bother trying to perfectly copy the profiles of the Lachenal reeds (particularly since my frame sizes don’t correspond exactly), but I used them as a general guide as to how thick to make the tip, the thinnest part of the belly, the shape of the profile, and how much force it takes to bend the tongue. The lowest reeds I made were lower than the bottom of the Lachenal set so I had to extrapolate the trend downwards.

Sound is terribly difficult to describe!

When I did my reeds (with a not-too-serious deadline breathing down my back) I simply looked closely at the corresponding Wheatstone reed (from which I had copied the width and length) and filed away – in a setup fairly close to yours: something clamping the tongue down on a plane. But since an “original” reed was right in front of me, it was easy to place that on the tuning bellows and compare.

For the higher reeds, the difference wasn’t too bad, but the lower you got…hmm. Lack of overtones.

At some point I’ll make a recording of the difference and send it to you.

Best regards,

/Henrik

I just discovered an interesting file, the “very smooth hand finishing file” made by Tomé Feteira. It’s probably a bit big for profiling but will definitely help with cleaning up the edges.

http://www.arceurotrade.co.uk/Catalogue/Cutting-Tools/Tome-Feteira-Files/Special-Files/Hand-Finishing-Files

Alex, I would second the recommendation for a single cut file if possible. I find with blunt files there is a tendency to push too hard in order to get a cut happening. This removes any subtlety in the filing and also on a longer reed it can mean distorting it slightly sideways, destroying the fit. Picking up a new file is always a pleasure. I get about 90 reeds to a file.

Thanks Chris! I have some single cut files and will give them another try.

Also, don’t worry about two hours a reed, it will speed up.