Bidirectional Reed Experiments

Recently I was asked to try to come up with a concertina reed that works in both directions, or at least to figure out why it hasn’t been done before. Ordinarily, a free reed only speaks when you suck air down past the tongue, into and through the vent in the frame. Most concertinas have a pair of reeds controlled by each button; one inside the reed chamber that only sounds on the pull stroke and another mounted on the underside of the reed pan that only sounds on the push stroke. Anglo instruments take advantage of this to play different notes on pull and push (this is known as bisonoricity), whereas English and Duet instruments play the same note in both directions so they need a pair of identical reeds for every button. If it was possible to make a bidirectional reed that worked as well as two standard reeds, it could potentially enable unisonoric instruments to be made smaller, lighter, and cheaper.

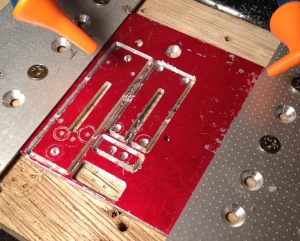

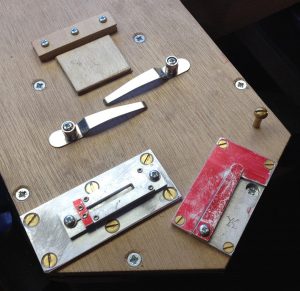

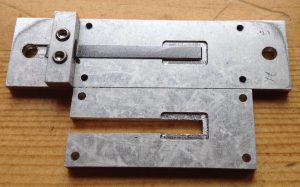

The way I went about solving the problem was to first build what was pretty much a standard reed in an oversized frame and check that it sounded normally in the suck direction, then screwed on a roughly horseshoe-shaped plate that fit around the tongue. I didn’t expect this to work because there was no way for a significant amount of air to get past the tongue to start the oscillation cycle, and indeed it didn’t.

I also modified my bellows bench a little to allow me to block up the standard dovetail socket and screw the new oversized frame to it elsewhere, and provided a means to block the one-way valve that normally releases air when I raise the bellows so that the rig only works in the suck direction.

Next I took the horseshoe back off and started experimenting with filing away various parts of the bottom of the horseshoe vent around the tongue, to provide some space for air to get to and past the tongue and allow it to start. Eventually I got it to sound, albeit poorly, in the suck direction, and it even made a tiny bit of sound in the push direction.

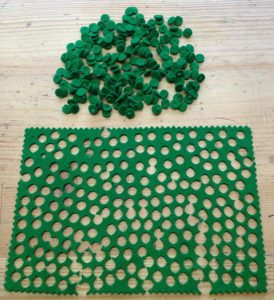

I had a theory that the triangular profile resulting from filing the underside of the horseshoe vent was causing the airflow to be cut off too gradually in the blow direction, so I next made a new horseshoe piece, this time with a square-sided recess milled into the underside so there was air space all around the tongue. This was supposed to cut the flow off more cleanly when the tongue swung up into the horseshoe vent.

This did work a little better, however it was very inefficient, very quiet, and worked much better in the suck direction than the blow direction. I figured that the reason it worked unequally was because the reed tongue was profiled only on the top surface, so when it passed into the bottom vent it cut the airflow cleanly and suddenly whereas when it passed into the top vent it cut it progressively from the tip towards the root.

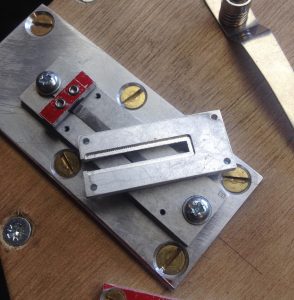

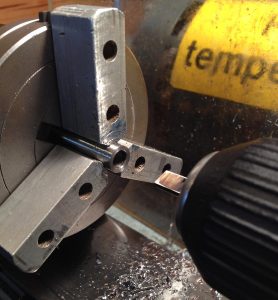

In order to try to solve this asymmetry, I built a second, more complicated, reed. On this one the reed tongue is set into the bottom frame by half the thickness of the reed stock, it is profiled equally on top and bottom of the tongue, and I also restricted the air pocket to the last third of the tongue, which I tried to profile fairly flat so that it cuts the airflow fairly cleanly in both directions.

The second reed was the most successful prototype I built, however it revealed the biggest flaw with the idea. When set up carefully it works pretty equally in both directions, however the amplitude is very limited compared to a standard reed:

I believe I now understand the reason for this, however it is a little tricky to explain. Before starting my experiments I had observed that with a standard reed playing at normal volume, the tongue swings well above and below the restriction point at the entrance to the vent. I imagined that with the bidirectional reed, it would swing past both restriction points and generate a similar amplitude level, perhaps with a different tone. This was based on a couple of misunderstandings about how reeds work.

My current understanding of what happens with a standard reed when it first starts up is that the tongue gets drawn down towards the frame (it needs to be set such that at rest there is a slight gap between the tongue and frame so air can start flowing). I don’t fully understand the physics behind why this happens, but it seems to me that the faster the airflow into the vent, the harder the tongue gets pulled down. The tongue descending towards the vent opening restricts the airflow into the vent, the force pulling the tongue down reduces, and the tongue springs back up, eventually peaking slightly higher than its rest position. Because it is higher, the gap between the tongue and the frame is larger and more air is able to flow through it than on the first cycle, so it gets drawn down a bit further, and springs back a bit higher than before. Over the course of a number of cycles, the amplitude builds up and up until the tongue is swinging a long way below the top of the vent. In order for this build-up to work, it’s important that every time the tongue swings a bit higher, it results in more air flowing through the vent, which causes the tongue to be pulled down harder and the amplitude of the oscillation to increase. Eventually the oscillation reaches an equilibrium level that depends on the pressure differential between the top and bottom of the reed frame. If you squeeze the bellows harder, the tongue oscillates to a greater height and the ‘packets’ of air being chopped up by the tongue passing through the frame are larger and more energetic, which results in a greater volume of sound from the instrument.

What goes wrong with my bidirectional reed that prevents it developing a decent amplitude at normal bellows pressure is that the second vent restriction, the one ‘above’ the tongue (whichever direction that happens to be), cuts off the air supply whenever the tongue tries to swing higher than the opening into the second frame. It’s impossible for the amplitude of the oscillation to ever build up any higher than the second frame, because it restricts the air supply as the tongue swings higher instead of allowing more air through. It is a lot like the governor on an engine, which throttles the fuel supply whenever it tries to exceed a certain speed.

It is possible to increase the amplitude at which the limiting occurs by increasing the distance between the two vent openings inside the reed, however there is a limit to how far you can take this. If the distance is too wide, the reed oscillations take several seconds to build up to an audible level, or never start up at all. It also becomes impossible to deliberately play the reed very quietly: you end up with a reed that has essentially no dynamic range.

To make matters worse, as well as the limited volume issue, there are several other disadvantages to this type of reed:

- They seem to be less efficient (i.e. they use more air than a standard reed operating at a similarly low amplitude), possibly because the way it is constructed to allow it to perform equally in both directions has the side effect of not cutting the airflow very cleanly in either direction.

- They are considerably more difficult to make than a unidirectional reed, probably something like 75% of the work of making a pair of standard reeds. A lot of the extra work has to do with making both frames a tight fit around the tongue without catching on the sides. Because nearly all of the cost of a hand-made reed like this is in labour time, it wouldn’t be a large cost saving to make an instrument with half the number of bidirectional reeds.

- They are significantly bigger and heavier than a standard reed because of the need to be able to screw the two parts together; you would save a little compared to a pair of standard reeds but not as much as you might think.

- There are a bunch of issues around the fact that what you would call the ‘set’ on a standard reed is fixed at manufacture-time by the relationship between the height of the recess and the thickness of the tip of the tongue. You can’t easily alter it deliberately, and it is possible to alter it accidentally as a side-effect of tuning the reed. It’s also important for the tongue to be set precisely central between the two frames, otherwise it starts poorly or not at all in one direction or the other.

- I don’t know for sure, but I suspect this design would be more susceptible than a standard reed to getting dust and fluff caught inside it and impeding its operation, because the air gets forced through a narrow recess inside the reed.

- It goes without saying that this type of reed is useless for an Anglo instrument because it produces the same note in both directions.

Following up on a slightly different line of inquiry, I made two final experimental reeds, one which only had a rectangular recess right at the tip, and another which was very similar but with a triangular recess instead. Neither of these worked as well as the second reed, I suspect because they only have a tiny amount of space for air to squeeze past the tongue. They sound in both directions (just about), but are very inefficient and quiet.

Here is an audio recording I made of the four experimental reeds plus a standard reed for comparison. The first reed had the second horseshoe fitted.

Although this work didn’t lead to a usable product, it was still a useful exercise for me in that I believe I now have a significantly better understanding of how concertina reeds actually work.