Glue Pot

I’m a fan of hot hide glue for musical instrument work. There’s no need to rehash the pros and cons of HHG versus liquid hide glue and modern synthetic glues like PVA; suffice it to say that it has been used successfully for millennia and I think there are very good reasons to continue using it for certain things including high-quality instruments.

To use HHG, you first dissolve it in water to make a gel, then heat it to about 60C (140F) to melt it. Too cold and the open time is reduced; too hot and it ‘cooks’, compromising the strength of the glue joint. Traditionally cast iron or brass double-boilers were used on a stove, an alcohol burner, or a charcoal brazier. Around the turn of the previous century somebody invented an electric glue pot, which used a thermostat and a heating element to maintain the correct temperature with much less fuss and risk of overheating the glue.

I know of two manufacturers still making electric glue pots. Hold Heet in the USA makes fairly large pots that are probably best suited for antique and reproduction furniture work. Herdim in Germany make smaller pots that seem to be targeted mainly at luthiers. From my research it seems that the Hold Heet pots are expensive in the US and very expensive in Europe, while the Herdim pots are expensive in Europe and very expensive in the US. Second hand electric glue pots of either brand never seem to come up on eBay in the UK, and it wouldn’t have made financial sense to import a used Hold Heet from the US and buy a 240V-110V transformer to power it. I strongly considered buying a new Herdim, and if money was no object that’s probably what I would have done.

If you search Google for alternatives to commercial electric glue pots, people have made them from various kinds of electric coffee pots, baby bottle warmers, old cast iron glue pots on electric hotplates, etc.

My new one is made from a mini deep fat fryer (0.5 litre oil capacity). I wasn’t happy with its built-in mechanical thermostat (it had about 15C of hysteresis and would probably have needed frequent adjustment), so I have instead hooked it up to a cheap Chinese PID temperature controller (a Rex C100 clone) with solid state relay output. This works remarkably well, regulating the temperature of the water bath to within a degree of the set temperature by pulsing a little bit of power into the heating element about once a second. I found I needed to set the water bath temperature several degrees higher than the desired glue temperature.

I knocked together a simple wooden box to hold the controller and the SSR, and a Perspex cover to hold the inner pot in position and prevent the water in the outer bath evaporating away. The light blue gaskets are made from two-part mouldable silicone rubber. The inner pot is a 0.25 litre Stewart Sealfresh screw-top food container. I have several of them and I cut a brush-sized hole in one of the lids to reduce the rate at which water evaporates from the glue in the pot.

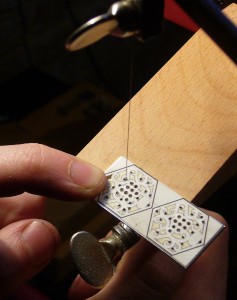

I also made several glue brushes in various sizes by whittling the handles from green wood and binding hog bristles to them with string. The smallest brush I made by boiling the end of the stick in water for five minutes, then smashing the fibres apart with a hammer: