No. 1: Brun Part 1: Introduction

For the past few months I have been hard at work designing and building my first concertina. It has been a long and at times difficult journey, and I have renewed respect for the Victorian pioneers of this complicated little instrument.

The inspiration came from my first client. He wanted something similar to an unusual rectangular 4 ½” by 6″ 24-button instrument developed in the 1850s by the Wheatstone company, the Duett. This was the first concertina with a duet button layout, i.e. one where the two ends have independent keyboards, with some overlap in range. The new instrument, however, was to have the Wikki-Hayden keyboard layout, as many buttons as I could fit in, riveted action, bigger bellows, nicer handles and straps, more attractive fretwork (but not the traditional acanthus-leaf style), and generally better build quality and finish.

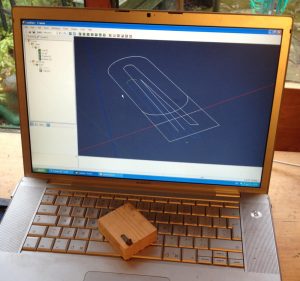

After many hours spent in CAD, laying out various different reed pans and action boards, I came to the conclusion that the most buttons I could practically fit in was thirty; fifteen per side. I could have just about squeezed in a couple more chambers into the right hand side reed pan underneath the keyboard array, but there was no way I could place pads over them on the action board. Thirty buttons is unusually small for a Hayden layout so the choice of which notes to include was always going to be a compromise. In consultation with Brian Hayden, I considered a few different layout options before settling on this one, on the basis that it should be usable in the most common folk music keys of C, G and D. The lowest note on the right hand side is middle C.

Over the next few posts, I’m going to cover how I developed and built the instrument.